Laszlo will have to wait. Tomorrow will be beyond imagining.

Laszlo will have to wait. Tomorrow will be beyond imagining.

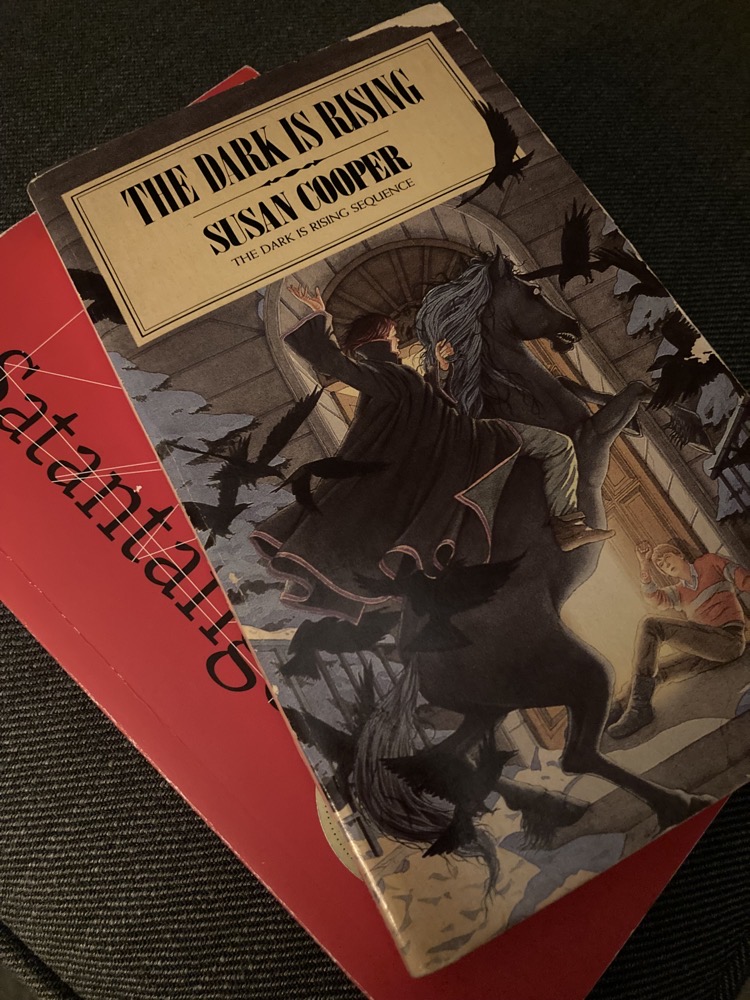

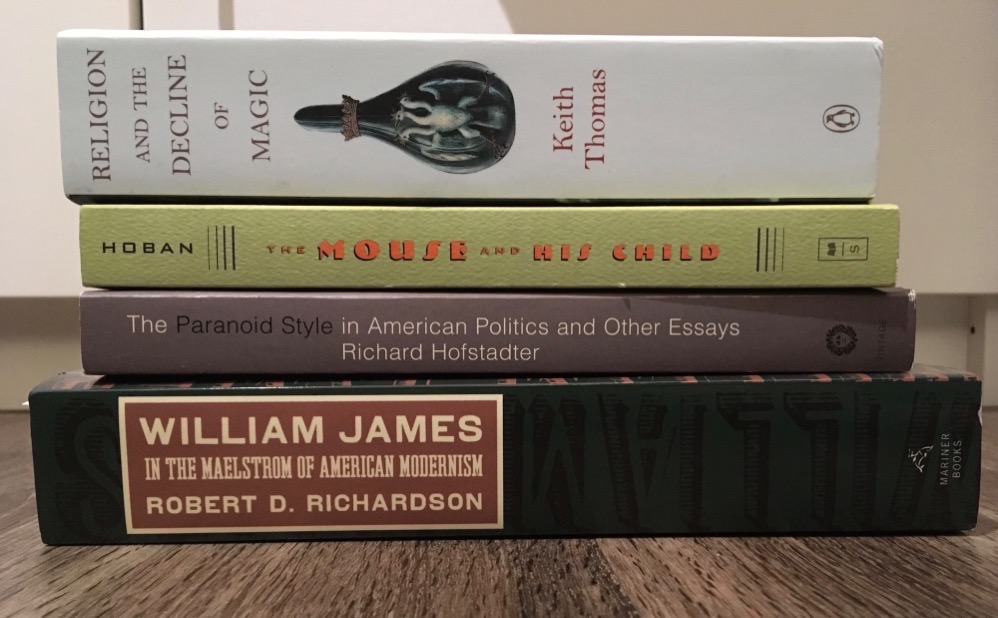

The books I brought with me, in case you were curious. (The Midgley is a reread.)

Today, I had to abandon a book on a topic I’ve been obsessed with for many years. The book is incredibly valuable: exhaustively researched, written by someone who’s a leading expert on the subject.

And yet…

The writing is atrociously, embarrassingly bad. I just couldn’t go on.

I was thinking about the early days of blogging, and remembered an old post from 2003. I reposted it a few years ago, but I took my archives offline earlier this year. (I’ve been republishing them gradually & selectively.)

Here is Blogs: A Brief Reader’s Guide, dead links & all.

🔗 Ken Knabb’s situationist archive is now housed in the Beinecke Library at Yale.

Q: Why was he doubly irritated?

A: Because he had forgotten and because he remembered that

he had reminded himself twice not to forget.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

These books arrived for xmas this year.

No poetry? No. I have sixty-eight books of poetry on my TBR shelf: thirty-seven I’ve started but not yet finished, and thirty-one others I haven’t even begun. (C’mon, I lived a 20-minute walk from Powells for five years; I can resist everything except temptation.)

My bring-along book for this trip has been the majestic Names on the Land, by George R. Stewart. I won’t be surprised if you haven’t heard of this man, but there have been several aspects of our world that he was directly or indirectly responsible for.

In 1941, he wrote a novel more or less from the point of view of a massive storm quite similar to the historic storm of a few weeks ago, sweeping in from the Pacific and raging across North America. In this novel, called Storm, a meteorologist is tracking the storm and in a moment of whimsy begins to refer to it as Maria (pronounced Mahr-ya). Soon after the book was published, the Weather Service introduced the convention of naming hurricanes not by the longitude & latitude at which they were first observed, but by a woman’s name.

Stewart was a native Californian and wrote many books of history in which the vast, the geologic, the global, is examined by focussing in on one small facet of the world. He wrote a study of US Hwy 40; of the final skirmish of the battle of Gettysburg; and many studies of various aspects of the westward migrations to Oregon and California throughout the 19th century. He also the definitive book on the Donner party’s plight, called Ordeal By Hunger.

His main concentration, however, was on names, both place names and given names.

Names on the Land has long been among my very short list of favorite books, and it has been of special interest this fall as we drove around the Hudson river valley in September, and now on this long drive into the West.

We watched, for example, as towns ending in -ville blossomed then gave away to -burg and -burgh as we drove through eastern Pennsylvania. The German settlers after the Revolutionary War were simply mad for -ville, and tacked it onto practically every town they settled in the last decades of the 18th century. Indeed, the new country was nuts for all things French, since they had played such a critical role in supporting the Colonies.

Another name that got tacked onto seemingly every county and town during those decades was that of General Washington. So, a town with a name that might otherwise sound a bit clunky and unimaginative, such as “Washingtonville,” very clearly reminds us of a time when our new country was bananas for our French allies, and swept up in a giddy adulation for a national hero the likes of which has hardly been matched since.

We also marvelled to read that a single summer’s expedition of several Frenchmen looking to discover the mythic river Missipi gave us the following names: Wisconsin, Peoria, Des Moines, Missouri, Osage, Omaha, Kansas, Iowa, Wabash, and Arkansas. No other expedition has had such a high success rate. Lewis & Clark, for instance, named everything in sight, of course, but the lag between their journey and the later migrations allowed nearly every one of their names to have faded. On the other hand, De Soto had travelled far more extensively than practically any other explorer of any age, but he apparently didn’t bother to name so much as a single creek or sandbar (or the Mississippi, although he was certainly the first European to see it and attest to its existence).

Those Frenchmen themselves left their own names (or others paid them the honor) all over my home region: Jolliet, Hennepin, Marquette. And another explorer, de la Salle, named the entire Mississippi watershed to honor the Sun-King with a single line in a letter home: Louisiane.

The French expedition indeed discovered the river, and sailed down from roughy what is now Stillwater to somewhere south of St Louis, but they failed to nail down a definitive name. In fact, it consistently bore three names among the seven explorers: the illiterate boatmen persisted in referring to it in the Indian style; Marquette called it “Conception” for the Immaculate Conception; and Jolliet called it “Buade” after one of his patrons back home in France. How “Mississippi” stuck and prevailed over not just the other two (admittedly shitty) candidates, but over the literally dozens of other names it bore, is a tale for another time.

Tonight, we are in Boise, Idaho. The name “Idaho” was almost the name for an earlier state. Other candidates for that territory were Yampa, Nemara, San Juan, Lula, Arapahoe, Weapollao, Tahosa; the “non-barbarian” candidates were Lafayette, Columbus, Franklin. The finalists, however, were Idahoe [sic] and Colorado. The latter won. But “Idaho,” without the final e, became a pet project of a California senator named Gwin, who thought it was an awful pretty name. He started shilling for it as the next few territories lined up for statehood and rechristening, including the Arizona territory, and it finally stuck on the western portion of the Montana territory. In reading the congressional record as the senators bickered about the relative merits of “Idaho” and “Montana” as names, you are reminded that the one thing Congress has consistently excelled at is whipping itself up into a furious and laughably righteous lather.

It is curious, too, that it took so long to name a state after Washington, given how consistently ape-shit Americans of all political persuasions have been for him over the years. That story, too, is for another time.

To dinner, and thence bed.

This dark morning, the rain lashes my front windows and Monstrance is on for at least the fourth time in the last twenty-four hours.

The Internet and all the channels on Blogovision are overrun with Vonnegut tributes and redundant notifications, so I will add my voice to the cacophony only to point toward this, by Lance Mannion. And to say, Exactly so: ruined. My life was ruined when I was about thirteen, when my eighth grade English teacher assigned Cat’s Cradle. Game over. I wanted to be a writer.

More than that, though, I wanted to stay awake and pay attention. There was something about Cat’s Cradle that made me realize I was constantly in danger of missing the big picture. It was the first of many books, and he was the first of many writers, to leave me with that sick yet elated feeling. Ursula K Le Guin, Douglas Adams, Ray Bradbury, Annie Dillard, Pynchon. It’s like the old joke about the difference between a virgin and a lightbulb: you can unscrew a lightbulb. You can’t unread stuff like that.

But you can fall back asleep. If I may be so bold as to suggest that art has a message (a claim I would not want to be asked to defend), that message is perhaps: Pay attention! Stay awake! They’re out there, waiting for you to fall asleep, and then they’re going to take over everything else! Keep your lamps trimmed and burning!

And for Vonnegut, like all satirists, the best defense is a good offense. Good artists shock, great artists startle. After all, we can grow numb to shocks, and fall back asleep. What we need are good and frequent startlings. Wake up.

In an attempt to slow down in my reading of ATD, I have been trying to distract myself in some way. But why should I want to try to slow down at all? Well, it is entirely possible that I was not in my right mind when I made the decision, but just before the blessed holiday season, I came to the conclusion that I needed to slow down on my reading of that vast tome because, well… Because as I approached the eponymously named Part 4, I felt as if I were engaged in a car chase from some hit action show in the 1970s, in which the laws of physics are ignored with blithe condescension. I was catching air over gentle rises in the street; bullets fired from extremely close range either glanced harmlessly off the bumper or missed altogether. It was like a syndicated rerun flying dream without the commercial breaks; it was awesome.

But once I actually hit Part 4, the car began to disintegrate entirely. The hubcaps zinged off onto the sidewalk; the trunk popped open and ejected its contents all over the road; the glove compartment gaped open suddenly, spitting countless scraps of paper out into the cab to flutter about, while the outdated maps flapped open to paste themselves to the windshield; the doors flew off; the tires shredded themselves on nothing, and tire rims began scraping and throwing sparks in dangerous directions…

It was perhaps time to slow down.

I have since been distracting my magpie mind with any number of dazzling distractions, chief among them Bleak House, which I had not read before. In fact, apart from Great Expectations in school maybe twenty-three years ago, I had never read any Dickens before. I’ve been really impressed. All I’ve read by the way of prose for the last eighteen months has been Proust and Pynchon, with some interludes for The Ginger Man and the White Whale. And I have in fact been a relative stranger to fiction for many years. My relish for Dickens may be nothing much more than of the “Is this a regular cracker or is this a Ritz?" variety. Ne’ertheless, I am relishing it all the same.

Other shiny things? A small Penguin sampler of John Ruskin, another fella I’d read not one word of before, but he’s been taking the top of my head right off. The book itself is slim and ridiculously overpriced, and you’ve probably seen them near the checkout of your local indie bookstore (the megaplexes tend to bury them deep in some counterintuitive section, like self-help or cooking; how these tumorous megastores stay in business boggles my poor naïve mind…) The erstwhile typographer in me was slain at the sight of them and has shown great restraint in not succumbing to their sirensong more than twice.

Also, I have a stack of Dostoevsky standing by for later in the year (some, like Crumbs-n-Puns & The Bros Kay, will be rereads after several decades; others, like the Idiot, for the first time). David Copperfield, Tom Jones, and The Red and the Black. Oh, and a collection of Guy Davenport’s writings (So far, I group him in the same polymathic camp as Louis Zukofsky and Paul Metcalf). I’ve also been hearing a compelling buzz abt Richard Powers, so I picked up his first book, the one about the farmers; also McCarthy’s Suttree. I have this habit of reading the first page of a book in the store; if it stays with me for a few days, it goes on my list (it’s a very long list). Suttree has been on that list for a while.

I highly recommend this review. It is spoilerish, if that’s a concern as you read through Against The Day yourself. This is exactly how it feels to trawl and drift through the book:

There is no narrator quite like Pynchon. The other evening I was up late with this book and it hit me, there in the deep quiet after everyone had gone to bed, that he’s really most like an all-night DJ, spinning his favorites, talking about them, riffing on this and that and not really caring too hard who’s listening. But like the best of those DJs, sometimes what comes out is so beautiful that your heart just jumps right into your throat.

Well, it is finished. After a 12-hour marathon yesterday, I completed the last volume of Á la recherche du temp perdu. I’m still a bit dazzled at the moment, not to mention more than a little exhausted. It may be some time before I can post anything resembling a debrief or final essay. For the moment, I will say that it was extremely rewarding, and that it is a profound work on every level — in its exquisite details, its discursive meanderings, its macrocosmic themes and ideas — which has changed, permanently, how I engage the world and myself.

Now, what’s next. Do you have to ask?

Okay, so Pynchon’s newest is now listed at Amazon as having 1120 pages, rather than the 992 as previously reported.

I finished MD. It was magnificent. Once Mason & Dixon begin the work of drawing the Line, the story takes several staggering turns, involving (among many other things) various nested fictions, not unlike The Saragossa Manuscript. There has only been a handful of books that, when I finish them, I have a nearly uncontrollable urge to start over again from the beginning. A Room of One’s Own was one; Fitzgerald’s Odyssey another; Walden of course; Moby-Dick. And now Mason & Dixon.

But instead, I have gone back to In Search of Lost Time. The main problem that I was having was, it turns out, with the translation of Sodom & Gomorrah. You will not be surprised if I tell you I have quite a bit of patience for shall we say thick prose, but S&G was turgid, convoluted, plodding… So I skimmed through the synopsis at the end, and moved on to Parts 5 and 6, The Prisoner and The Fugitive, bound together in one volume. And it is the Proust I remember from Guermantes and especially from Young Girls.

I’m sure I can be done with the last one thousand pages of Proust not too long after Against the Day is released. And it’s only 1120 pages long: how hard can it be?

Climbing thru Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon, (MD) and have been for roughly the last month. It’s been interrupted by a number of other texts, including The Wandering Scholars, by Helen Waddell, and the incandescent Consolation of Boëthius, and if I don’t get a move on, there will be other seasonal reads (esp. Tripmaster Monkey) to divert it.

At the end of July, I finished Vineland (VL) for what apparently was the first time. I had bought it breathlessly in 1990, right when it first came out, but I now realize I couldn’t possibly have gotten beyond the first thirty or so pages. Someone I thought was the main protagonist essentially vanishes abt that far into the book, not to return until almost the very end.

VL is generally pretty good, if a bit “lite” – it reads at times as if Tom Robbins were half-heartedly trying his hand at a Pynchon impersonation.

I am finding MD a far more mature and measured work even than GR. He can veer from Restoration satire (people bustling in and out of rooms, breathless maids with ripp’d bodices (bodices, in fact, designed to rip open and snap back closed again) thwarted lovers exiting precipitously thru windows) to trenchant observations on the corrosive effects of slavery on culture, often within the same paragraph.

It is written in the diction, grammar, phrasing, and spelling of an 18th century text, but also includes such bemusing phantasms as a talking dog, and wry anachonisms as the first anchovy pizza in England, as well as a 2 or 3 page discussion of “modern” music, ending with this great punchline (you will see, of course, the dazzling bait-and-switch):

“…Much of your Faith seems invested in this novel Musick–"

”Where better?" asks young Ethelmer confidently. “Is it not the very Rhythm of the Engines, the Clamor of the Mills, the Rock of the Oceans, the Roll of the Drums in the Night, why if one wish’d to give it a Name,–”

“Surf Music!" DePugh cries.

After we read about Mason & Dixon observing the 1761 Transit of Venus from the Dutch colonies of South Africa (during which a comically tragic portrait of racism and slavery is drawn with deft and bitter strokes), the two then depart for America to demarcate the disputed property line between Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware.

This, their arrival in America, where everything is for sale, and people stay up all night in coffeeshops; here, in the seething, sprawling metropolis of Philadelphia (then second only to London among English-speaking cities of the earth), is where the satire and fantasy really kicks in. We meet, for example, the irrepressible Dr Franklin, always wearing sunglasses of differing hues, playing his Armonica in nightclubs, and rousing the latenight crowd out into lightning storms.

I am in the midst of a section wherein the two surveyors, standing in various farmers' back gardens, are attempting, with little success, to explain the mathematical and political causes of this geometric nightmare. It’s not just Pynchon’s own tangential writing that obscures the greedy human motives behind such tortured lines.

Okay, one more passage:

Every day the room [of the Coffeeshop], for hours together, sways on the verge of riot. May unchecked consumption of all these modern substances at the same time, a habit without historical precedent, upon these shores be creating a new sort of European? less respectful of the forms that have previously held Society together, more apt to speak his mind, or hers, upon any topic he chooses, and to defend his position as need be? Two youths of the Macaronic profession are indeed greatly preoccupied upon the boards of the floor, in seeking to kick and pummel, each into the other, some Enlightenment regarding the Topick of Virtual Representation. An individual in expensive attire, impersonating a gentleman, stands upon a table freely urging sodomical offenses against the body of the Sovereign, being cheered on by a circle of Mechanics, who are not reluctant with their own suggestions. Wenches emerge from the scullery dimnesses to seat themselves at the tables of disputants, and in brogues as thick as oatmeal recite their own lists of British sins.

773 delicious pages of this.

I don’t know if I can stand the wait. (See this, and this as well.)

So much for the pattern; up until M&D, his books alternated between encyclopedic, historical sprawls and shorter, “contemporary” things focussing on NoCal. But the newest thing, said to be called Against the Day, is nearly a cool grand (992 pp), and judging by what few descriptions there are (including Pynchon’s own blurb), it is every bit as vast as the Big Three.

Speaking of vast, I’m taking another breather from Proust – only 1700 pages into it, and already it has formed a strong seasonal bond with long winter nights. My reading & rereading habits are often seasonal. Summer inspires me to reread Thoreau and the Odyssey (trnsl. Fitzgerald), and now I’ve been sucked into Crime & Punishment for the first time since 1989. Riveting! But all that, and the others stacked up around me, may have to wait while I dive into Mason & Dixon: it’s the only one I haven’t yet read, even once. I despair: I’m in the middle of about thirty books right now. Faster Pussycat: Read, read!

Based on the actuarial tables, I only have maybe 35 or 40 more years. Assume two books a month; that’s still only just under 1000 books. And what about rereads, which is essential for any good book? (e.g. either read Walden ten times or not at all.) Do they count toward the total? This is a terrible line of thought. If no more new books came out ever again, there are still well over 5000 books I NEED to read. Not to mention the ones I need to write. Who has time for work, let alone eating or sleeping? And dammit: we have Season 2 of Sports Night in the house – that’s time away from reading, too! Can I have some clones, please, like in Calvin & Hobbes?

I finished V.

It is the 20th century in microcosm. People are on obsessive quests for something they don’t understand, and which may be nonexistent; who believe their personal meaning-making can somehow illuminate the wider, meaningless universe – indeed, that simply because they make a connection between two things, they come to think that the connection exists empirically. The Authorities (governments, churches, corporations, aka “Them”) who are obsessed with the clean, the polar, the binary, the unhuman: plastics, robotics; who praise the individual, then crush it. And how delightful to reflect that nothing much has changed since 1204, except They have gotten even more powerful, by making us all think that we have. A great trick right out of Lao-tzu’s playbook: fill their bellies and empty their heads. We are all fated to die, masked and anonymous, pinned beneath the rubble in the basement of some unknown Mediterranean city, as the feral children strip us of our jewels. So remember, in only a few billion years, none of this will matter. In the meantime: go to church, buy your polyester and medications, and vote against your own interests.

Back to Proust with a vengeance; with Boëthius' Consolation, Henrick’s Te Tao Ching and the Tractatus for light distractions.

And still it rains.

So, I finished GR last night. So much more beautiful and obscene than I could possibly have fathomed as a callow teenager. And I have glimpsed more finely now the roots for so many of the esthetic choices in my life. “Keep cool, but care.”

The Shakedown is now between V. and resuming Sodom & Gomorrah a dozen or so pages on from where I left off. My mind is still reeling from GR, and there are more than a few overlapping characters and elements, so I may just have to dig in. My copy of V. is a disintegrating Perennial edition from 1986. It’s already lost the half-title page. The binding glue has calcified and is dropping off in little white flecks. I have paperbacks from the 1950s that are in better shape. Shameful. But I’ll make due.

Research for my prose pieces continues, and consumes most of my so-called free time. The minute I don’t want to learn anything new, someone shoot me. (As my neighbor said, tipsy from his second brandy alexander, if you stop moving, you’re dead.) Volcanoes; the Fisher King; the West India Company; the I Ching; the river IJssel; film terms and the history of cinema; the Iliad; medieval satires. Put it all in a pot, along with the medieval and modern ideas of evil (which are, delightfully, almost complete opposites), and you have something rather fun. And I’m reading Ruskin and Boëthius, too.

GR is still going strong: Slothrop is about to ditch his pig suit, so Marvy’s castration and the bombing of Hiroshima are only hours away; it is so much richer than I ever appreciated when last I read it, in the late 80s. Amazing what a difference of 19 years can make. The collective cultural deathwish; dehumanization thru the industrialization of everything; apocalyptic obsession with polarities: themes that have only gotten more terrifyingly relevant since August 6th, 1945.

Only thru gentleness, thru staying on the edges, thru pledging allegiance to softness, diversity, complexity, can we even begin to hope to find some unmarked exit out of this nightmare.

I remain hopeful only because (as Tolkien points out) despair assumes a foreknowledge that is by definition impossible, and is therefore as hubristic as that of the masters of war, who cling to deathlike certainties as fearfully as do the pacifist nihilists…

Time isn’t a line, or even a thing (tho saying can make it seem so); history cannot come to an end (tho histories can); ideas can (and indeed must) be forgotten, and the mountains and rivers persist; the cosmos (or what you will) is fleeting: it flows, and moves on, and we can scarcely step into it even once.

Gilbert Sorrentino has died. As of 9:30 am EDT, however, I can only find the Wikipedia article as corroboration of this posting.

The theologian Jaroslav Pelikan has also died. Obits here and here. I first encountered him while I was a student living in Aberdeen. I attended as many of his Gifford lectures as I could in the spring of 1992. The lectures I attended focussed on the Cappadocian fathers, Basil and the Gregs (good name for a band, no? playing the Divinity circuit).

Oh, and I read the Da Vinci Code last Sunday afternoon. The whole thing. Is this what all those mass market paperbacks you can buy in grocery stores and airports are like? It was only slightly more entertaining than an episode of E! True Hollywood Story, slightly less intellectually strenuous than watching someone get a haircut, and staggeringly inept in its history. I found it plainly, baldly, distressingly bad on so many levels. It was, as one of my coworkers likes to say, “craptastic.” So this reviewer’s take on the Da Vinci movie does not surprise me: “In the cinema, such matters are best left to Monty Python.”

So. The Proust has stalled. This is okay with me; I need time to digest all that has happened. I reached the end of Vol 3 at the end of January, and decided to take a few weeks off. I read Moby-Dick for what I think was the fifth time; then I finished The Master and Margarita, which had been an xmas present; then I drowsed thru Don Quixote; I put that down midway through while upstate last month, where I bought and read the incandescent Ginger Man by JP Donleavy. After finishing that, I gulped down Eco’s newest book, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. There is, here, an online annotation project for all its millions of allusions and references. I learned of the Loana project from The Modern Word… where I couldn’t help but notice the Thomas Pynchon pages.

Now, people who’ve known me long enough may know of my teen obsession with Pynchon. It was, in fact, twenty years and one month ago that I bought Gravity’s Rainbow. 12 April 1986. I read it two times in succession, and one more time in college. I attempted it again without success some time in the late 90s, and then one more time in the summer of 2000. I couldn’t take it. Giggling fratboy jokes, I thought, and backshelved all my Pynchon.

But something happened as I clicked around the Pynchon page, and felt myself getting all wispy and nostalgic. Three weeks ago, I bought a new copy of The Crying of Lot 49 (the old one, like my copy of V., had long since disintegrated (strangely appropriate for an author so preoccupied with paranoia and entropy)) and dove in. And I loved it. It was actually human. And exuberant. The comedy was a welcome antidote to the lugubrious earnestness of modern “mainstream” fiction, a genre I had vowed I would never commit myself to again. So I pulled GR out, and started. Why not? What’s the worst that will happen? I’ll still find it too reminiscent of my hypereducated adolesencce, or it will make me vomit, and that will be that.

But that wasn’t that. Two weeks later, I’m on page 365. It’s a lark. By turns slapstick, philosophical, vivid, vague…

I am reclaiming old parts of myself. All this spring, as I relearn who I am, in light of deeply saddening revelations, I have been going back to the poetry, music, and prose of my youth and finding that little of it deserves the backshelved neglect it’s received. When did I decide I wasn’t allowed to like what I like?

I am a surrealist. The world is so irredeemably sick and tragic, and the surest way to wither to Bartlebian nothingness is to take it seriously. Instead, we must be like Charles Halloway and draw a smile on the wax bullet, to kill the October Queen. We mustn’t cry because of the world, but laugh in spite of it.

Laughter is a rebellious act. If the world is straight, we must bend it with comedy, which is, of course, the most serious way to face the world.

So I reclaim comedy, the absurd, the impossible, the hopeless. After all: it’s funny!

I finished The Guermantes Way a few days ago, after roughly ten weeks of reading. In Search of Lost Time is divided into seven parts, but because Parts 5 and 6 are fairly short, they are bound together. So in reaching the end of Volume 3, I think of myself as half way through. It is appropriate, therefore, that I take a moment and reflect on the book so far.

The Guermantes Way focused on a series of social encounters over the course of two years or so. The narrator has left behind his childish crush on Gilberte, and his adolescent obsession with Albertine, and now finds himself mesmerized by the Duchesse de Guermantes. He stalks her for many months, and in a double attempt to forget her and ingratiate himself with her family in the hope of being invited into her salon, he visits for several weeks one of his very good friends, Robert Saint-Loup, who is a nephew of the Duchesse.

His ardor for the Duchesse finally cools over the course of the next half year, and only then does he finally get invited to one of her parties. He is approached by the eccentric M. de Charlus, another Guermantes. He is an aloof, pompous, and, frankly, creepy old man. The narrator does not keep an appointment with Charlus because he learns that his grandmother has had a stroke. She dies early in the second part, or about halfway through the volume, but we do not hear much about it. Instead, we see how others react, or don’t react. The Duc de Guermantes stops by during the grandmother’s final hours and is left waiting in the hall because the rest of the family is rushing about, calling for servants to bring boiling water, or fresh towels, or more medications. The Duc, oblivious of the crisis, and perplexed that there could possibly be anything more important than a visit from a Guermantes, is extremely offended and goes away with the impression that the narrator’s mother is a distant and antisocial woman who does not know how to run a good house.

In all, the portraits of high society are deeply unflattering; vain and childish fools hide behind grandiose titles. The Proustian habit, established in the first two volumes, of delving into long, discursive reflections and descriptions of peoples' innermost motivations is often abandoned in Guermantes, in favor of straightforward narrative. It is less introspective and more purely driven by narrative than the previous volumes. Many characters' personalities are laid bare through simple descriptions of their actions and words.

So it was a shock yesterday and today to find that Volume 4, Sodom and Gomorrah, returns to the simultaneously microscopic and macrocosmic reflections on human nature. This volume marks the beginning of what Proust called the “great inversion.” Our perception of many characters, beginning with M. de Charlus, are altered utterly through a series of revelations regarding their hidden motives and relationships.

If the principal themes of Swann’s Way were that of childhood and memory (and the introduction of later themes, such as senseless obsessive love), and In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower was that of adolescent puppy love, and The Guermantes Way was the glittering and worthless surfaces of high society, then Sodom and Gomorrah is that of homosexual love. It also begins the reprise of unthinking obsession, first stated relatively mildly in the backstory of Swann, the social-climbing Jew who is passing for a gentile, and Odette, the erstwhile prostitute and courtesan who is clawing her way into society. This time, it is the narrator who finds himself increasingly obsessed and jealous of Albertine, and not Albertine as she is, but Albertine as he imagines her to be, just as Swann has little notion of Odette’s past, and no inclination to find out.

The overall experience of reading Proust is a wrenching one. He is unsparing in his critiques and insights into human behavior; his portrayal of teen love was, for example, pitch-perfect and embarrassingly accurate. I find myself recasting my own life upon reflection. I also find myself recalling events in my own life that had otherwise fallen into oblivion. He describes the sensation of lying awake at night as a child, watching the faint lights seep in through the windows, or around the edges of the door, and I remember my own insomniac anxiety: the gold and glass chandelier over the stairs, the tan carpet, the distant adult voices downstairs.

Reading Guermantes has been, like the previous volumes, a great comfort, but unlike them, a mild torture. Proust’s acuity in portraying the quotidian nature of hypocrisy is devastating. Every relationship in this volume is in one way or another unhealthy, doomed, loveless, mercenary. The Duc, for example, is an incorrigible philanderer, cycling rapidly through gold-digging courtesans, who, when inevitably they are cast off, become confidantes and “ladies-in-waiting” to the spurned Duchesse. The Duc is kind to the Duchesse only when he has discarded a mistress or when he’s beginning to woo a new one. But they are a formidable social team, bound together by deep habit and ancient obligation, and so they entertain together. He serves as the Duchesse’s impresario; her wit is bitter and funny, and he sets up the marks for her to strike down with her sharp tongue.

Another theme relates to the utter divorce between loyalty and reason. The events in the book take place during the height of the Dreyfus Affair. Whether you thought Dreyfus innocent or guilty had almost nothing to do with the facts of the case, which were few and largely indisputable, and had almost everything to do with your social standing, your political sympathies, and, of course, whether you were Jewish or not, and Anti-semitic or not. Just as Swann finds himself blindly obsessed with Odette, despite knowing full well that the tart is a sly, self-serving, faithless whore, and not even remotely his type, so did royalists and conservatives unthinkingly condemn Dreyfus against all reason, and supporters of Dreyfus instinctively dismiss anti-Dreyfusards as worthless and mindless wastes of skin, regardless of their other virtues. It was to French society what the debate over abortion has been for the US in the last several decades.

This is what is so wrenching about Proust: the silly, the callow, the perverted, the vain, the noble, the naïve… they all are me, they all are us.

I may go to a book (poems or prose or fiction) to read new evocations or descriptions of what I already know, believe, feel; or I may go in order to discover new perspectives, previously unkown or unfamiliar ways of thinking, feeling, belief.

But if I am too eager for the one and encounter the other, I probably won’t like the work — it’ll have nothing to do with the quality of the writing or the value of the thinking, the depths of feeling and everything to do with my own expectations, needs, tastes of the moment. I may dismiss the work utterly simply because we are mismatched just then: twenty-four hours earlier or later, and it might have become a seminal and life-changing work.

In the last week or so, I advanced to Volume 2 of In Search of Lost Time. So far, we have returned to the youthful narrator’s perspective, and we are hearing about his naïve love for Swann’s daughter, Gilberte. We are also gaining more insights into Swann’s obsessive and disastrous affair with Odette, and we understand a little better how they came to be married, despite Swann having arrived at the sobering realization, at the end of Swann in Love, that Odette really just isn’t his type.

And Proust continues to do a very strange thing with the point of view; he regularly slides from his own first-person account of things to an omniscient narrator privy to everyone’s internal motivations and back again. He somehow manages to do this fluidly, without the slightest jolt to the narrative; we simply shift from, say, a dinner party at which the narrator is present, to deep background regarding events from years before the narrator would even have been born.

I experience no jolt because, I think, of the absolute trust he inspires. He could tell me about anything, however dull or otherwise not to my taste, and I’d happily listen for as long as he wished to speak, because he has proven beyond doubt that he can make insightful and profound use of anything at all, including wallpaper, furniture, mediocre Romantic sonatas — and of course madeleines dipped in herbal tea.

By a curious coincidence, my wife spotted a Proust reference in an unlikely spot. As a ramp up to the imminent theatrical release of its sequel, some cable channel has been repeatedly airing an action flick called The Transporter. At one point, a character bakes some madeleines, prompting a revery from the French police chief on the nature of memory and observation, noting that Proust, being a “details man,” would have made a great detective; he adds that in fact it had been his reading of Proust as a youth that inspired him to become an investigator.

She had just told me of this scene when we turned on the TV — and there was the movie, moments away from the very scene in question. And in a typically Proustian way, I experienced the scene twice — but the first one seemed more real, because it had been Ana’s story, and the actual film itself, upon which her version was based, seemed like a mere enactment.

(The silly Python song faded weeks ago, thankfully — except when my wife asks me, “And in the second book: what did Proust write about, write about?")

Mere pages away from the end of Swann’s Way — so close in fact that I don’t know if I should even haul it to work or not; I could finish it on the ride in this morning, and I hate lugging dead books with me. Volume 2 is somewhat larger, so I sure as heck don’t want to drag them both. Ah, the quandaries of a reader.

But more about the book itself:

It is breathtaking. He slows time down for you to draw out, over many pages, the refractions of a single moment. The narrator sees, for example, a girl through the hedge, falls instantly in love, and we then read about how the mind so often latches onto some framing detail, the colors of the leaves and flowers in the hedge, the flash of a beach ball, the sound of some distant wind high in the trees, as the crucial mnemonic detail that will forever stand in for the luminous flashing moment of first love. The mind can only grasp that first moment by approaching as it were obliquely, by way of some indirect and innocuous aspect.

The novel within a novel, Swann in Love, which I just finished, is a study of sexual jealousy, agonizing and embarrassing in its brutal and lacerating accuracy. A trainwreck in dreamlike slow motion. And Odette isn’t even his type.