It’s been a busy week.

It’s been a busy week.

Goodbye, tiny apartment.

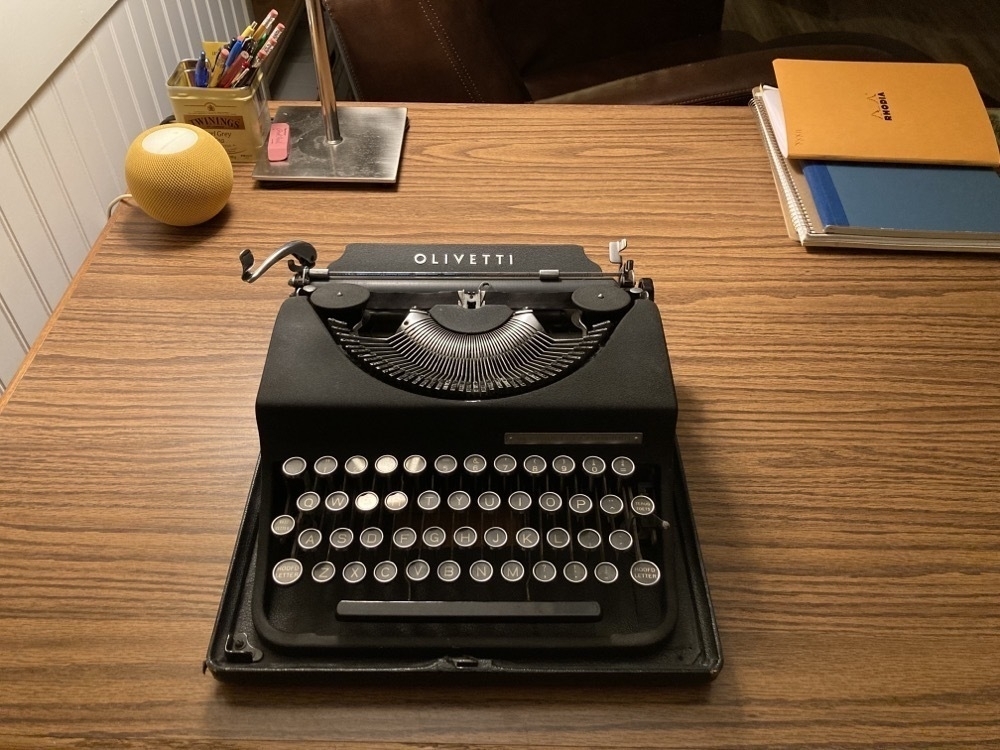

After six years on a shelf, my old Olivetti has a room of its own.

We just moved into our house.

We just bought a house.

First and last afternoons.

1 July 2011 at 1:30pm:

30 March 2016 at 2:35pm:

I’ve been curious why, when people here on the coast say they are travelling to Portland, that they are going “up to Portland.”

Because I am over-educated and under-employed, I’ve had a lot of time to think about this curious figure of speech. On a map, Portland is very clearly southeast of Clatsop County. Like it or not, speakers of English speak of north as up, and south down. So why not say “down to Portland”? Also, when approaching Portland from over the coastal range, you are descending a long slope. This too draws on a different but related notion of down.

Having read way far more Mircea Eliade than was strictly good for me, I couldn’t help but recall Eliade’s observation that many ancient societies regarded their holiests sites as being closer to heaven than profane places, even when they were not situated on literal peaks. The temple mount in Jerusalem, Mt Zion, Baghdad, etc etc. Eden was in the east, which is why for the bulk of history, east was up, and maps were often drawn with the east at the top. We still pay homage to this old custom when we speak of orienting ourselves, and orientation. Orient = east.

So, do residents of Clatsop County look upon Portland as their cultural capital? (After all, even today, Britons regularly speak of going up to London, even though almost the entire country is north of London.)

No. (Or, if they do, that’s not why they say up.) The answer is much simpler, and the geography of my home region kept me from seeing it.

People on the coast say up because, living at the mouth of the Columbia, Portland is upriver from them. The Columbia is the only American river worth mentioning that empties into the Pacific (indeed, it is one of only a handful of rivers in the world that empties into the Pacific). The shipping trade that passes in and out keeps this town alive. I knew how important the Columbia is to this region, and it’s not surprising that the major geographical and political features of a region will affect how people speak of their local environments… So why didn’t I think of that?

Well, I grew up on the Mississippi. Downriver is south – down. Upriver is north – up. And my hometown of Minneapolis turned its back on the river that birthed it years ago: the city’s skyline now looks out over the lakes, away from the river.

Also, a continent, seen simplistically, is a domed rock that slopes down to the sea. But this would not have been a useful metaphor for someone like me, living so far from any ocean.

The place that made us, even if we no longer live there, even if it no longer exists, will continue to shape our worldview, and influence which metaphors we live by, as we struggle every day to understand our surroundings.

If we grow up in a region where all rivers flow south, then we may come to think of that local feature as a universal law, and we will be blind to very real rivers that do not conform to this “law.” A benign mistake, surely. But if we equate up with good and up with north, we will necessarily and unconsciously equate good with north. This is why syllogisms can sometimes be more trouble than they’re worth.

And it reminds us always to ask ourselves why we think what we think, and in what ways our models of the world both bring order to and distort our apprehension of the very world we hope to understand.

What time is it, really? Our laptops, checking in with the atomic clock, updated their times automagically. So when I looked at the bedside clock, it should have been an hour later than the computers.

But they were the same. Had the bedside clock synchronized itself, too? Apparently. What a world.

By the end of the day, we will have set our clocks back twice: once for daylight saving time, and once for passing from Mountain to Pacific. Won’t shorten the miles, however.

As we leave the urban sprawls behind us in the east, the sky is once again a fact rather than an implication.

I have been delighted and relieved to see Venus as the morning star most mornings this week. And at night, there are more than about sixteen stars visible. Actual constellations, rather than broad asterisms. I have been able to keep track of the Moon’s phase without the use of a widget on my computer.

I may even be able to get my telescope out after six long years, dust it off, and look again at the icecaps on Mars, at Jupiter’s moons, at Saturn’s ears…

My bring-along book for this trip has been the majestic Names on the Land, by George R. Stewart. I won’t be surprised if you haven’t heard of this man, but there have been several aspects of our world that he was directly or indirectly responsible for.

In 1941, he wrote a novel more or less from the point of view of a massive storm quite similar to the historic storm of a few weeks ago, sweeping in from the Pacific and raging across North America. In this novel, called Storm, a meteorologist is tracking the storm and in a moment of whimsy begins to refer to it as Maria (pronounced Mahr-ya). Soon after the book was published, the Weather Service introduced the convention of naming hurricanes not by the longitude & latitude at which they were first observed, but by a woman’s name.

Stewart was a native Californian and wrote many books of history in which the vast, the geologic, the global, is examined by focussing in on one small facet of the world. He wrote a study of US Hwy 40; of the final skirmish of the battle of Gettysburg; and many studies of various aspects of the westward migrations to Oregon and California throughout the 19th century. He also the definitive book on the Donner party’s plight, called Ordeal By Hunger.

His main concentration, however, was on names, both place names and given names.

Names on the Land has long been among my very short list of favorite books, and it has been of special interest this fall as we drove around the Hudson river valley in September, and now on this long drive into the West.

We watched, for example, as towns ending in -ville blossomed then gave away to -burg and -burgh as we drove through eastern Pennsylvania. The German settlers after the Revolutionary War were simply mad for -ville, and tacked it onto practically every town they settled in the last decades of the 18th century. Indeed, the new country was nuts for all things French, since they had played such a critical role in supporting the Colonies.

Another name that got tacked onto seemingly every county and town during those decades was that of General Washington. So, a town with a name that might otherwise sound a bit clunky and unimaginative, such as “Washingtonville,” very clearly reminds us of a time when our new country was bananas for our French allies, and swept up in a giddy adulation for a national hero the likes of which has hardly been matched since.

We also marvelled to read that a single summer’s expedition of several Frenchmen looking to discover the mythic river Missipi gave us the following names: Wisconsin, Peoria, Des Moines, Missouri, Osage, Omaha, Kansas, Iowa, Wabash, and Arkansas. No other expedition has had such a high success rate. Lewis & Clark, for instance, named everything in sight, of course, but the lag between their journey and the later migrations allowed nearly every one of their names to have faded. On the other hand, De Soto had travelled far more extensively than practically any other explorer of any age, but he apparently didn’t bother to name so much as a single creek or sandbar (or the Mississippi, although he was certainly the first European to see it and attest to its existence).

Those Frenchmen themselves left their own names (or others paid them the honor) all over my home region: Jolliet, Hennepin, Marquette. And another explorer, de la Salle, named the entire Mississippi watershed to honor the Sun-King with a single line in a letter home: Louisiane.

The French expedition indeed discovered the river, and sailed down from roughy what is now Stillwater to somewhere south of St Louis, but they failed to nail down a definitive name. In fact, it consistently bore three names among the seven explorers: the illiterate boatmen persisted in referring to it in the Indian style; Marquette called it “Conception” for the Immaculate Conception; and Jolliet called it “Buade” after one of his patrons back home in France. How “Mississippi” stuck and prevailed over not just the other two (admittedly shitty) candidates, but over the literally dozens of other names it bore, is a tale for another time.

Tonight, we are in Boise, Idaho. The name “Idaho” was almost the name for an earlier state. Other candidates for that territory were Yampa, Nemara, San Juan, Lula, Arapahoe, Weapollao, Tahosa; the “non-barbarian” candidates were Lafayette, Columbus, Franklin. The finalists, however, were Idahoe [sic] and Colorado. The latter won. But “Idaho,” without the final e, became a pet project of a California senator named Gwin, who thought it was an awful pretty name. He started shilling for it as the next few territories lined up for statehood and rechristening, including the Arizona territory, and it finally stuck on the western portion of the Montana territory. In reading the congressional record as the senators bickered about the relative merits of “Idaho” and “Montana” as names, you are reminded that the one thing Congress has consistently excelled at is whipping itself up into a furious and laughably righteous lather.

It is curious, too, that it took so long to name a state after Washington, given how consistently ape-shit Americans of all political persuasions have been for him over the years. That story, too, is for another time.

To dinner, and thence bed.

Twelve hours on the road, ten hours driving. The headwinds dropped, the land levelled out, and we maintained much higher speeds for longer stretches. Today was much more like our old roadtrips, and giving ourselves an early evening yesterday was a big part of today’s success.

More massive windmill farms. More pickups driven by cowboy hats. More mountains. Then no mountains. The Rockies tack north and west up the continent, so after our first brush with them, they disappeared again for most the afternoon and evening. Southern Wyoming is flat but gently rolling, with vast panoramas opening out at the most surprising moments. We were usually around 6000 feet above sea level, and we crossed the continental divide twice (or maybe we crossed two of the continental divides once each, I don’t know for sure).

It’s unlikely we’ll have another day tomorrow like today, but if we do, we could be in extreme eastern Oregon tomorrow night. We have options. As I keep saying: as long as we don’t arrive more tired than when we drove away last week; just as tired is fine.

Tomorrow morning: breakfast in Little America at a sprawling and deliciously kitchy travel center, where we’ll buy some goofy postcards.

As we drove north to pick up I-80 outside Cheyenne today, we finally returned to a familiar roadbed after many days on I-70 (which we had only driven on once before, and then only much farther east). But we couldn’t quite remember how familiar I-80 was. So we began counting it up, and eventually ran up a tally of most of our long roadtrips.

This is what we could remember:

1997

1998

1999

2000

2003

2004

Those roadtrips in the 18 months between June 2003 and September 2004 totalled just under 19,000 miles. That’s an average of 1,000 miles per month . . . And this is the sixth time we’ve driven on I-80 between Cheyenne & Salt Lake City.

We are in Salina, Kansas, hoping to make it somewhere near Denver. After a few days on the road, we have better on-the-ground numbers of our daily progress, what we do, what we can do. And, with great sadness, we have decided the California leg of our journey will have to go. After Salt Lake City, we’ll bank north onto I-84 and head straight for Warrenton. (But we comfort ourselves in knowing that the Bay Area is a long weekend away now, rather than a costly transcontinental flight.)

Pictures tonight.

Hello from a Starbucks in Independence, Missouri. We are making both better and worse time today than yesterday. Better because the roads are smoother, straighter, flatter. We also topped up Hestur’s tires because they’d been looking low. It’s much more reponsive now, and we can maintain higher speeds. Worse because there is a high wind cutting across the highway, and with less to break it, we’re weaving around a bit.

And because we are really quite tired. Every now and again, as we drive along, we get a flash of the “big picture,” and we remember that 2010 was really kinda rough. And then with the push to get packed up . . . Well, let’s just say we fall dead asleep at night and have to stop every two hours or so during the day.

Well, we’re done with our mochas: it’s time to hit the road again.

Well, we made it. Cambridge, Ohio. Our first really full day of driving. Too much of it after dark, however, so we’re planning an early departure tomorrow so we can pack it in not long after dark tomorrow evening. We want to make it as far into Illinois as we can; St Louis would be ideal.

Pictures? Amusing anecdotes? Are you kidding? Maybe tomorrow.

We only made it as far as eastern Pennsylvania Saturday night, and we decided to stay two nights and really rest up. We really needed it. The truck needed a little repacking, and we needed lots of naps.

The Martin Guitar factory is just up the road in Nazareth, so we’re going to go up there to snoop around for a while before hitting the road around lunchtime. There are guided tours every day, too. They allow photography, so expect a few pictures.

We’re aiming for eastern Ohio for tonight.

We made it: we got on the road with a van packed literally to the roof.

Did we say we’d hit the road by 10?

Well, we did.

10 PM.

It is three in the morning. We are in Bethlehem, PA, at a Comfort Inn (there was no room at the manger).

That bad joke is about all I have energy for. We plan on sleeping in, so look for more lively accounts of recent events (and more bad jokes, no doubt) tomorrow.

A week from this evening, we hope to be in a hotel somewhere in Ohio, our first day’s drive behind us. We’re aiming straight for St Louis on I-78 & I-70 to follow (if only for a while) portions of the original Oregon Trail.

(missing picture)

Rather than banking north on the west side of Missouri, we will continue straight for Denver. Only then will we head north, picking up I-80 to take us through Wyoming and on down past Salt Lake City.

I’m excited about the next bit, which will take us on the only stretch of I-80 we’ve never been on: Salt Lake City to San Francisco. As well as allowing us to complete our first full traverse of a bi-coastal interstate highway (10 and 90 are the only others), this route will also take us across a remarkable geologic phenomenon in Nevada called the Basin & Range. It is so called because the particular manner in which Navada is ripping apart causes the crust to break up into long strips which then tip and topple, forming row after row of basins divided by long ranges. They resemble the crests of a windswept sand dune, but on a completely different scale. Geology repeats itself, because, as I understand it (i.e. barely at all), what’s happening right now in Nevada happened in New Jersey perhaps a quarter of a billion years ago: Africa and North America pulled apart, leaving the newly formed Appalachians on one side, and the newly formed Atlas Mountains on the other. Geology repeats itself.

Anyway.

We will spend a few wine-soaked days in the Bay Area, and finally sprint north on I-5 for Portland and our final destination of Warrenton. No strategy survives the battlefield, so while the route is almost certainly going to look more or less exactly like this . . .

(missing picture)

. . . it’s anyone’s guess how long exactly the trip will take.

(A loaded Econoline × no cruise control × our exhaustion level) ÷ (the pure adrenaline rush of being on the road × the excitement of starting our new life) = X

Ten days, maybe?

Meet Hestur, our main transport for the upcoming emigration:

It’s a 1999 Ford E150 Econoline. We’re the second owners. The original owner bought it to continue moonlighting his plumbing business even though he had already more or less retired. It is in excellent shape because he hardly drove it, and treated it very well.

More pix will follow, clearly displaying the space in the back and the shelves and cubbies for plumbers' gear. Fab!

I’m referring to Hestur as “it” – but “he” and “she” are equally acceptible. Such is the malleability of inanimate objects: we project onto them whatever strange archetypes that haunt the darker corners of our psyches, like shadows on the back of a cavewall.

“Hestur” is Icelandic for horse, and as I understand it, the word is masculine and can refer to stallions specifically. So he would be appropriate in this case. But of course, all vessels seem to be female so, along with the homonym “Hester,” she would work just as well. And since our Hestur is a lovely shade of red, the allusion to Hester Prynn’s notorious letter isn’t completely out of line. (But not having read the book for maybe 25 years, I can’t recall: she ain’t a twit like Emma Bovary, is she? I hope not.)