Happy 50th to Gravity’s Rainbow.

Happy 50th to Gravity’s Rainbow.

Thomas Pynchon, Against the Day (pp 1000–01):

“We will buy it all up,” making the expected arm gesture, “all this country. Money speaks, the land listens, where the Anarchist skulked, where the horse-thief plied his trade, we fishers of Americans will cast our nets of perfect ten-acre mesh, leveled and varmint-proofed, ready to build on. Where alien muckers and jackers went creeping after their miserable communistic dreams, the good lowland townsfolk will come up by the netful into these hills, clean, industrious, Christian, while we, gazing out over their little vacation bungalows, will dwell in top-dollar palazzos befitting our station, which their mortgage money will be paying to build for us. When the scars of these battles have long faded, and the tailings are covered in bunchgrass and wildflowers, and the coming of the snows is no longer the year’s curse but its promise, awaited eagerly for its influx of moneyed seekers after wintertime recreation, when the shining strands of telpherage have subdued every mountainside, and all is festival and wholesome sport and eugenically-chosen stock, who will be left anymore to remember the jabbering Union scum, the frozen corpses whose names, false in any case, have gone forever unrecorded? who will care that once men fought as if an eight-hour day, a few coins more at the end of the week, were everything, were worth the merciless wind beneath the shabby roof, the tears freezing on a woman’s face worn to dark Indian stupor before its time, the whining of children whose maws were never satisfied, whose future, those who survived, was always to toil for us, to fetch and feed and nurse, to ride the far fences of our properties, to stand watch between us and those who would intrude or question?” He might usually have taken a look at Foley, attentive back in the shadows. But Scarsdale did not seek out the eyes of his old faithful sidekick. He seldom did anymore. “Anarchism will pass, its race will degenerate into silence, but money will beget money, grow like the bluebells in the meadow, spread and brighten and gather force, and bring low all before it. It is simple. It is inevitable. It has begun.”

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow:

Don’t forget the real business of war is buying and selling. The murdering and violence are self-policing, and can be entrusted to non-professionals. The mass nature of wartime death is useful in many ways. It serves as spectacle, as diversion from the real movements of the War. It provides raw material to be recorded into History, so that children may be taught History as sequences of violence, battle after battle, and be more prepared for the adult world. Best of all, mass death’s a stimulus to just ordinary folks, little fellows, to try ’n’ grab a piece of that Pie while they’re still here to gobble it up. The true war is a celebration of markets.

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow:

In one of these streets, in the morning fog, plastered over two slippery cobblestones, is a scrap of newspaper headline, with a wirephoto of a giant white cock, dangling in the sky straight downward out of a white pubic bush. The letters

MB DRO ROSHI

appear above with the logo of some occupation newspaper, a grinning glamour girl riding astraddle the cannon of a tank, steel penis with slotted serpent head, 3rd Armored treads ’n’ triangle on a sweater rippling across her tits. The white image has the same coherence, the hey-lookit-me smugness, as the Cross does. It is not only a sudden white genital onset in the sky — it is also, perhaps, a Tree…

Happy 85th to Thomas Pynchon!

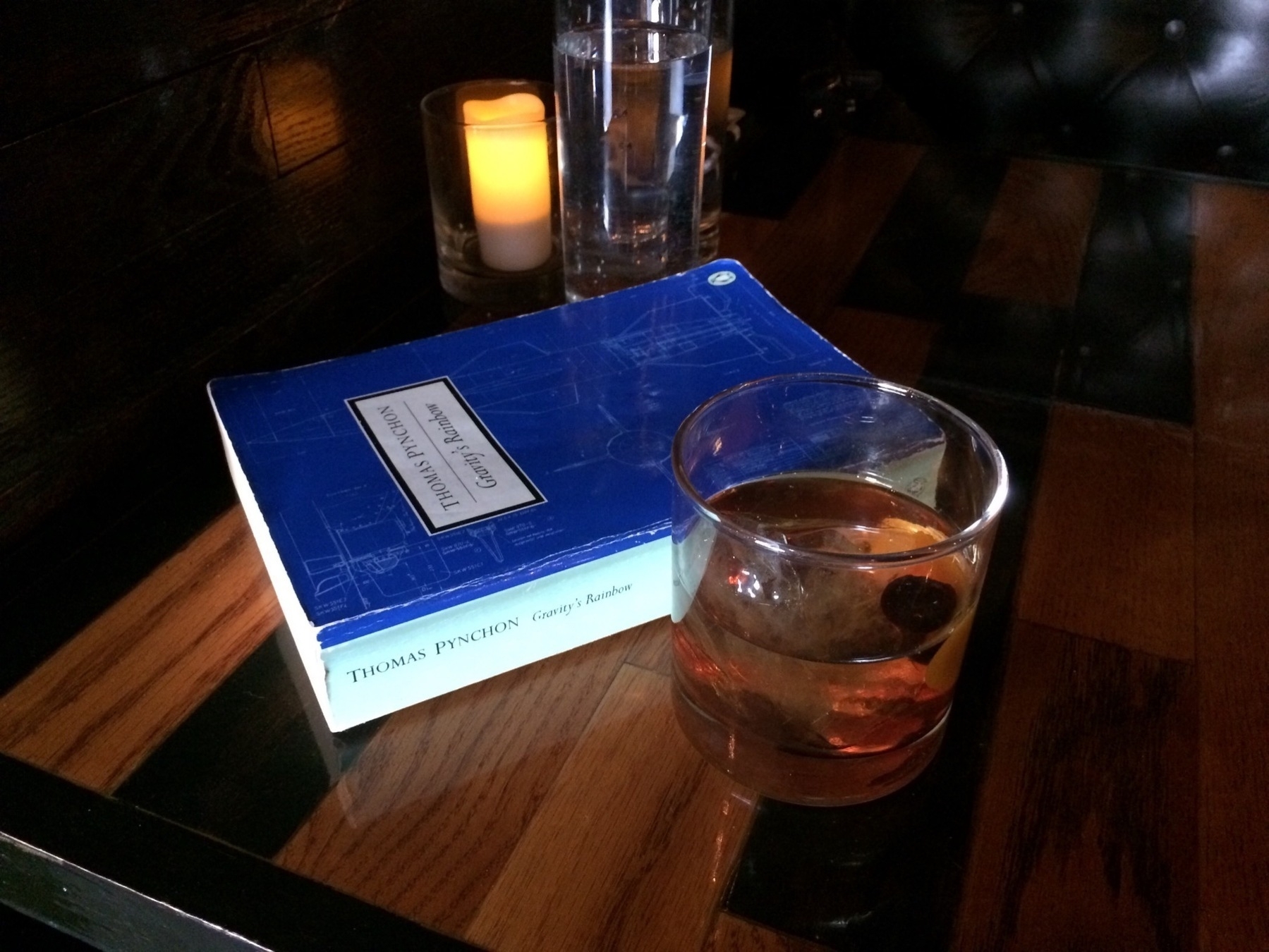

I’m not going out today (too much to do at home) so here’s a photo from a previous Pynchon in Public Day—

—at the excellent Volstead Speakeasy in (of all places) Eagan.

Keep cool but care.

If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.

—Thomas Pynchon, born on this day in 1937, and who’s been sporting a face mask for years:

In an attempt to slow down in my reading of ATD, I have been trying to distract myself in some way. But why should I want to try to slow down at all? Well, it is entirely possible that I was not in my right mind when I made the decision, but just before the blessed holiday season, I came to the conclusion that I needed to slow down on my reading of that vast tome because, well… Because as I approached the eponymously named Part 4, I felt as if I were engaged in a car chase from some hit action show in the 1970s, in which the laws of physics are ignored with blithe condescension. I was catching air over gentle rises in the street; bullets fired from extremely close range either glanced harmlessly off the bumper or missed altogether. It was like a syndicated rerun flying dream without the commercial breaks; it was awesome.

But once I actually hit Part 4, the car began to disintegrate entirely. The hubcaps zinged off onto the sidewalk; the trunk popped open and ejected its contents all over the road; the glove compartment gaped open suddenly, spitting countless scraps of paper out into the cab to flutter about, while the outdated maps flapped open to paste themselves to the windshield; the doors flew off; the tires shredded themselves on nothing, and tire rims began scraping and throwing sparks in dangerous directions…

It was perhaps time to slow down.

I have since been distracting my magpie mind with any number of dazzling distractions, chief among them Bleak House, which I had not read before. In fact, apart from Great Expectations in school maybe twenty-three years ago, I had never read any Dickens before. I’ve been really impressed. All I’ve read by the way of prose for the last eighteen months has been Proust and Pynchon, with some interludes for The Ginger Man and the White Whale. And I have in fact been a relative stranger to fiction for many years. My relish for Dickens may be nothing much more than of the “Is this a regular cracker or is this a Ritz?" variety. Ne’ertheless, I am relishing it all the same.

Other shiny things? A small Penguin sampler of John Ruskin, another fella I’d read not one word of before, but he’s been taking the top of my head right off. The book itself is slim and ridiculously overpriced, and you’ve probably seen them near the checkout of your local indie bookstore (the megaplexes tend to bury them deep in some counterintuitive section, like self-help or cooking; how these tumorous megastores stay in business boggles my poor naïve mind…) The erstwhile typographer in me was slain at the sight of them and has shown great restraint in not succumbing to their sirensong more than twice.

Also, I have a stack of Dostoevsky standing by for later in the year (some, like Crumbs-n-Puns & The Bros Kay, will be rereads after several decades; others, like the Idiot, for the first time). David Copperfield, Tom Jones, and The Red and the Black. Oh, and a collection of Guy Davenport’s writings (So far, I group him in the same polymathic camp as Louis Zukofsky and Paul Metcalf). I’ve also been hearing a compelling buzz abt Richard Powers, so I picked up his first book, the one about the farmers; also McCarthy’s Suttree. I have this habit of reading the first page of a book in the store; if it stays with me for a few days, it goes on my list (it’s a very long list). Suttree has been on that list for a while.

Here’s a thought I just had. To collate and then read all of Pynchon’s works chronologically.

It would go something like this:

[Note, 5 July 2020: I have inserted Inherent Vice and Bleeding Edge, neither of which had been published when I first wrote this post.]

I highly recommend this review. It is spoilerish, if that’s a concern as you read through Against The Day yourself. This is exactly how it feels to trawl and drift through the book:

There is no narrator quite like Pynchon. The other evening I was up late with this book and it hit me, there in the deep quiet after everyone had gone to bed, that he’s really most like an all-night DJ, spinning his favorites, talking about them, riffing on this and that and not really caring too hard who’s listening. But like the best of those DJs, sometimes what comes out is so beautiful that your heart just jumps right into your throat.

Okay, so Pynchon’s newest is now listed at Amazon as having 1120 pages, rather than the 992 as previously reported.

I finished MD. It was magnificent. Once Mason & Dixon begin the work of drawing the Line, the story takes several staggering turns, involving (among many other things) various nested fictions, not unlike The Saragossa Manuscript. There has only been a handful of books that, when I finish them, I have a nearly uncontrollable urge to start over again from the beginning. A Room of One’s Own was one; Fitzgerald’s Odyssey another; Walden of course; Moby-Dick. And now Mason & Dixon.

But instead, I have gone back to In Search of Lost Time. The main problem that I was having was, it turns out, with the translation of Sodom & Gomorrah. You will not be surprised if I tell you I have quite a bit of patience for shall we say thick prose, but S&G was turgid, convoluted, plodding… So I skimmed through the synopsis at the end, and moved on to Parts 5 and 6, The Prisoner and The Fugitive, bound together in one volume. And it is the Proust I remember from Guermantes and especially from Young Girls.

I’m sure I can be done with the last one thousand pages of Proust not too long after Against the Day is released. And it’s only 1120 pages long: how hard can it be?

Climbing thru Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon, (MD) and have been for roughly the last month. It’s been interrupted by a number of other texts, including The Wandering Scholars, by Helen Waddell, and the incandescent Consolation of Boëthius, and if I don’t get a move on, there will be other seasonal reads (esp. Tripmaster Monkey) to divert it.

At the end of July, I finished Vineland (VL) for what apparently was the first time. I had bought it breathlessly in 1990, right when it first came out, but I now realize I couldn’t possibly have gotten beyond the first thirty or so pages. Someone I thought was the main protagonist essentially vanishes abt that far into the book, not to return until almost the very end.

VL is generally pretty good, if a bit “lite” – it reads at times as if Tom Robbins were half-heartedly trying his hand at a Pynchon impersonation.

I am finding MD a far more mature and measured work even than GR. He can veer from Restoration satire (people bustling in and out of rooms, breathless maids with ripp’d bodices (bodices, in fact, designed to rip open and snap back closed again) thwarted lovers exiting precipitously thru windows) to trenchant observations on the corrosive effects of slavery on culture, often within the same paragraph.

It is written in the diction, grammar, phrasing, and spelling of an 18th century text, but also includes such bemusing phantasms as a talking dog, and wry anachonisms as the first anchovy pizza in England, as well as a 2 or 3 page discussion of “modern” music, ending with this great punchline (you will see, of course, the dazzling bait-and-switch):

“…Much of your Faith seems invested in this novel Musick–"

”Where better?" asks young Ethelmer confidently. “Is it not the very Rhythm of the Engines, the Clamor of the Mills, the Rock of the Oceans, the Roll of the Drums in the Night, why if one wish’d to give it a Name,–”

“Surf Music!" DePugh cries.

After we read about Mason & Dixon observing the 1761 Transit of Venus from the Dutch colonies of South Africa (during which a comically tragic portrait of racism and slavery is drawn with deft and bitter strokes), the two then depart for America to demarcate the disputed property line between Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware.

This, their arrival in America, where everything is for sale, and people stay up all night in coffeeshops; here, in the seething, sprawling metropolis of Philadelphia (then second only to London among English-speaking cities of the earth), is where the satire and fantasy really kicks in. We meet, for example, the irrepressible Dr Franklin, always wearing sunglasses of differing hues, playing his Armonica in nightclubs, and rousing the latenight crowd out into lightning storms.

I am in the midst of a section wherein the two surveyors, standing in various farmers' back gardens, are attempting, with little success, to explain the mathematical and political causes of this geometric nightmare. It’s not just Pynchon’s own tangential writing that obscures the greedy human motives behind such tortured lines.

Okay, one more passage:

Every day the room [of the Coffeeshop], for hours together, sways on the verge of riot. May unchecked consumption of all these modern substances at the same time, a habit without historical precedent, upon these shores be creating a new sort of European? less respectful of the forms that have previously held Society together, more apt to speak his mind, or hers, upon any topic he chooses, and to defend his position as need be? Two youths of the Macaronic profession are indeed greatly preoccupied upon the boards of the floor, in seeking to kick and pummel, each into the other, some Enlightenment regarding the Topick of Virtual Representation. An individual in expensive attire, impersonating a gentleman, stands upon a table freely urging sodomical offenses against the body of the Sovereign, being cheered on by a circle of Mechanics, who are not reluctant with their own suggestions. Wenches emerge from the scullery dimnesses to seat themselves at the tables of disputants, and in brogues as thick as oatmeal recite their own lists of British sins.

773 delicious pages of this.

I don’t know if I can stand the wait. (See this, and this as well.)

So much for the pattern; up until M&D, his books alternated between encyclopedic, historical sprawls and shorter, “contemporary” things focussing on NoCal. But the newest thing, said to be called Against the Day, is nearly a cool grand (992 pp), and judging by what few descriptions there are (including Pynchon’s own blurb), it is every bit as vast as the Big Three.

Speaking of vast, I’m taking another breather from Proust – only 1700 pages into it, and already it has formed a strong seasonal bond with long winter nights. My reading & rereading habits are often seasonal. Summer inspires me to reread Thoreau and the Odyssey (trnsl. Fitzgerald), and now I’ve been sucked into Crime & Punishment for the first time since 1989. Riveting! But all that, and the others stacked up around me, may have to wait while I dive into Mason & Dixon: it’s the only one I haven’t yet read, even once. I despair: I’m in the middle of about thirty books right now. Faster Pussycat: Read, read!

Based on the actuarial tables, I only have maybe 35 or 40 more years. Assume two books a month; that’s still only just under 1000 books. And what about rereads, which is essential for any good book? (e.g. either read Walden ten times or not at all.) Do they count toward the total? This is a terrible line of thought. If no more new books came out ever again, there are still well over 5000 books I NEED to read. Not to mention the ones I need to write. Who has time for work, let alone eating or sleeping? And dammit: we have Season 2 of Sports Night in the house – that’s time away from reading, too! Can I have some clones, please, like in Calvin & Hobbes?

I finished V.

It is the 20th century in microcosm. People are on obsessive quests for something they don’t understand, and which may be nonexistent; who believe their personal meaning-making can somehow illuminate the wider, meaningless universe – indeed, that simply because they make a connection between two things, they come to think that the connection exists empirically. The Authorities (governments, churches, corporations, aka “Them”) who are obsessed with the clean, the polar, the binary, the unhuman: plastics, robotics; who praise the individual, then crush it. And how delightful to reflect that nothing much has changed since 1204, except They have gotten even more powerful, by making us all think that we have. A great trick right out of Lao-tzu’s playbook: fill their bellies and empty their heads. We are all fated to die, masked and anonymous, pinned beneath the rubble in the basement of some unknown Mediterranean city, as the feral children strip us of our jewels. So remember, in only a few billion years, none of this will matter. In the meantime: go to church, buy your polyester and medications, and vote against your own interests.

Back to Proust with a vengeance; with Boëthius' Consolation, Henrick’s Te Tao Ching and the Tractatus for light distractions.

And still it rains.

So, I finished GR last night. So much more beautiful and obscene than I could possibly have fathomed as a callow teenager. And I have glimpsed more finely now the roots for so many of the esthetic choices in my life. “Keep cool, but care.”

The Shakedown is now between V. and resuming Sodom & Gomorrah a dozen or so pages on from where I left off. My mind is still reeling from GR, and there are more than a few overlapping characters and elements, so I may just have to dig in. My copy of V. is a disintegrating Perennial edition from 1986. It’s already lost the half-title page. The binding glue has calcified and is dropping off in little white flecks. I have paperbacks from the 1950s that are in better shape. Shameful. But I’ll make due.

Research for my prose pieces continues, and consumes most of my so-called free time. The minute I don’t want to learn anything new, someone shoot me. (As my neighbor said, tipsy from his second brandy alexander, if you stop moving, you’re dead.) Volcanoes; the Fisher King; the West India Company; the I Ching; the river IJssel; film terms and the history of cinema; the Iliad; medieval satires. Put it all in a pot, along with the medieval and modern ideas of evil (which are, delightfully, almost complete opposites), and you have something rather fun. And I’m reading Ruskin and Boëthius, too.

GR is still going strong: Slothrop is about to ditch his pig suit, so Marvy’s castration and the bombing of Hiroshima are only hours away; it is so much richer than I ever appreciated when last I read it, in the late 80s. Amazing what a difference of 19 years can make. The collective cultural deathwish; dehumanization thru the industrialization of everything; apocalyptic obsession with polarities: themes that have only gotten more terrifyingly relevant since August 6th, 1945.

Only thru gentleness, thru staying on the edges, thru pledging allegiance to softness, diversity, complexity, can we even begin to hope to find some unmarked exit out of this nightmare.

I remain hopeful only because (as Tolkien points out) despair assumes a foreknowledge that is by definition impossible, and is therefore as hubristic as that of the masters of war, who cling to deathlike certainties as fearfully as do the pacifist nihilists…

Time isn’t a line, or even a thing (tho saying can make it seem so); history cannot come to an end (tho histories can); ideas can (and indeed must) be forgotten, and the mountains and rivers persist; the cosmos (or what you will) is fleeting: it flows, and moves on, and we can scarcely step into it even once.

So. The Proust has stalled. This is okay with me; I need time to digest all that has happened. I reached the end of Vol 3 at the end of January, and decided to take a few weeks off. I read Moby-Dick for what I think was the fifth time; then I finished The Master and Margarita, which had been an xmas present; then I drowsed thru Don Quixote; I put that down midway through while upstate last month, where I bought and read the incandescent Ginger Man by JP Donleavy. After finishing that, I gulped down Eco’s newest book, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. There is, here, an online annotation project for all its millions of allusions and references. I learned of the Loana project from The Modern Word… where I couldn’t help but notice the Thomas Pynchon pages.

Now, people who’ve known me long enough may know of my teen obsession with Pynchon. It was, in fact, twenty years and one month ago that I bought Gravity’s Rainbow. 12 April 1986. I read it two times in succession, and one more time in college. I attempted it again without success some time in the late 90s, and then one more time in the summer of 2000. I couldn’t take it. Giggling fratboy jokes, I thought, and backshelved all my Pynchon.

But something happened as I clicked around the Pynchon page, and felt myself getting all wispy and nostalgic. Three weeks ago, I bought a new copy of The Crying of Lot 49 (the old one, like my copy of V., had long since disintegrated (strangely appropriate for an author so preoccupied with paranoia and entropy)) and dove in. And I loved it. It was actually human. And exuberant. The comedy was a welcome antidote to the lugubrious earnestness of modern “mainstream” fiction, a genre I had vowed I would never commit myself to again. So I pulled GR out, and started. Why not? What’s the worst that will happen? I’ll still find it too reminiscent of my hypereducated adolesencce, or it will make me vomit, and that will be that.

But that wasn’t that. Two weeks later, I’m on page 365. It’s a lark. By turns slapstick, philosophical, vivid, vague…

I am reclaiming old parts of myself. All this spring, as I relearn who I am, in light of deeply saddening revelations, I have been going back to the poetry, music, and prose of my youth and finding that little of it deserves the backshelved neglect it’s received. When did I decide I wasn’t allowed to like what I like?

I am a surrealist. The world is so irredeemably sick and tragic, and the surest way to wither to Bartlebian nothingness is to take it seriously. Instead, we must be like Charles Halloway and draw a smile on the wax bullet, to kill the October Queen. We mustn’t cry because of the world, but laugh in spite of it.

Laughter is a rebellious act. If the world is straight, we must bend it with comedy, which is, of course, the most serious way to face the world.

So I reclaim comedy, the absurd, the impossible, the hopeless. After all: it’s funny!

The news of John Spencer’s death makes me very sad.

Ever since Bartlet walked out of the Oval, having signed over his presidential powers to the Speaker of the House, I have hardly watched the show because, to quote Sam, “they forgot to bring the funny.”

But for a few years there, that show was deeply important to me, out of all proportion for a television show. It was important to me the way the Daodejing is important to me, or Gravity’s Rainbow. And the role of Leo McGarry was pivotal to its importance. Leo was the basso continuo.

Raise a glass to his memory.